On Designing Livable Cities for All

And how data can empower community organizers to create more resilient and equitable cities

Look around any major urban center like San Francisco or Los Angeles and you’ll see a smattering of green space. From Golden Gate Park to Griffith Park, public parks are oases in a growing sea of concrete that provide home to local wildlife, a recreational space for all, and most importantly, a tool for urban heat reduction and carbon sequestration.

When you think about climate tech, it often conjures an image of technical hardware — heat pumps or industrial machinery that can suck carbon dioxide right out of the atmosphere. But what if capable technology already existed and found product market fit millions of years before humans existed?

Trees are still the most effective and affordable way to sequester carbon. On average, a single tree sequesters 50 lbs of carbon dioxide a year. Over the average 40-year lifespan of most urban trees, that’s roughly 1 ton of carbon dioxide per tree. With an estimated 5.5 billion trees in urban areas alone, you get 137.5 million tons of carbon sequestered from the atmosphere from urban forests every single year and 5.5 billion tons over 40 years — a small investment with a big ROI.

But that’s not all — trees have other valuable features. Foliage cleans the air, trunks store carbon, roots prevent erosion, and canopies create a natural cover to shield people and buildings from heat, which is critically needed in overheating urban environments around the world.

Urban heat islands kill

As a life-long Californian (and reluctant Modesto-native), I’ve experienced my fair share of 100 degree weather. Heat is often accompanied by years of drought and subsequent water use reduction measures — brown lawns are in vogue and drought friendly plants are symbols of pride. In fact, 23 million Americans live in places at risk of extreme heat, and over 118 million Americans face at least 26 days of temperatures over 90 degrees a year.

Studies have shown that when there are more than 3 consecutive days of 90 degree weather, heat-related illness and death increase, estimating that annually 20,000 premature deaths are linked to hot temperatures. And as a greater share of the American population migrates to cities, the infrastructure cost to keep people safe will also grow. Groundbreaking technologies like energy-efficient heat pumps and even mechanical trees seem promising, but the clear solution is already at work — all it takes is smarter urban planning.

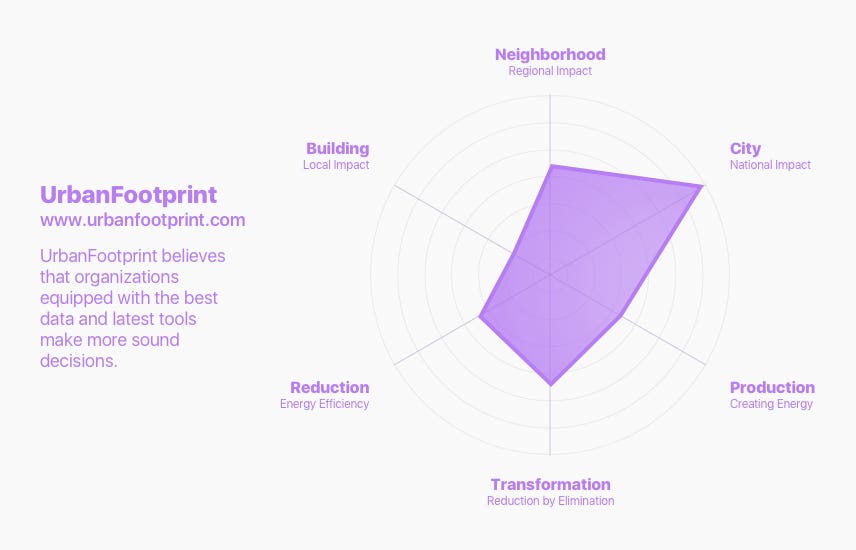

UrbanFootprint, a cheat sheet to healthier cities

5 years ago, David Nowak published Declining urban and community tree cover in the United States and spurred heavy media coverage on the decline of tree cover and the impacts to our climate and public health. Today, as heat records are broken nearly annually, the conversation has again turned to trees as a tool to protect city dwellers from summer heat, but now planners have better resources to tackle these issues head on.

UrbanFootprint, a leader in an emerging SaaS vertical focused urban data, has created a platform that makes nationwide, sector-specific data available to the planners controlling the design of our built & natural environment. Among the sector-specific data subscriptions that UrbanFootprint offers is a collection of attributes focused on ESG. The data manages and reports on land use attributes such as parks and tree coverage within urban regions and creates scenarios that help cities maintain environmental diligence in their climate action plans.

Turning data into equitable greenways

Would you believe me if I told you that 40% of heat-related deaths could have been avoided through increased tree coverage alone? Despite a growing overall number of trees, tree canopy coverage is falling behind due to rapid urbanization. To connect urban sprawl around the country, cities are pouring concrete faster than they are planting trees.

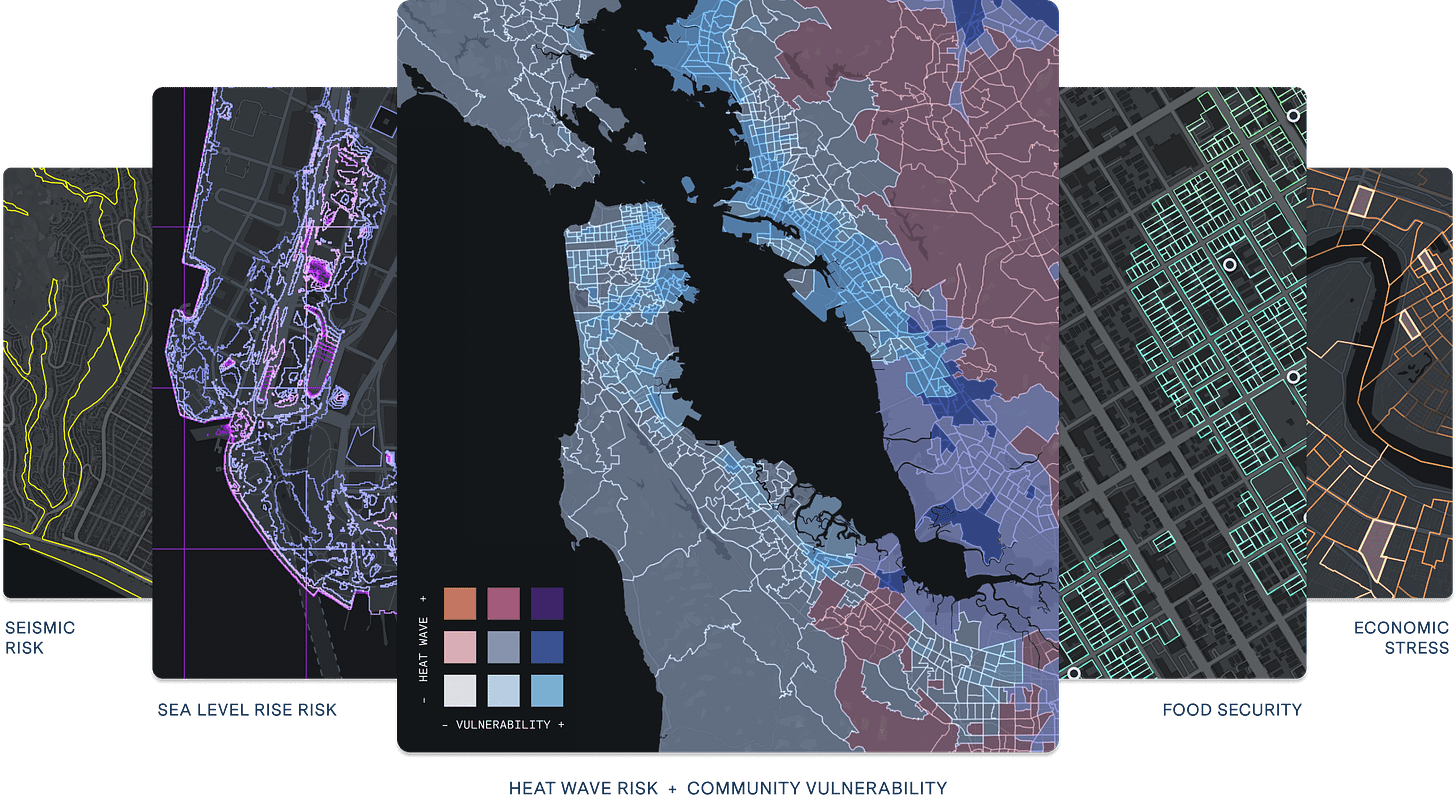

As cities develop their urban forest plan, tools like UrbanFootprint can bring attention to the interplay of urban data layers that may be overlooked:

Heat wave patterns throughout the year

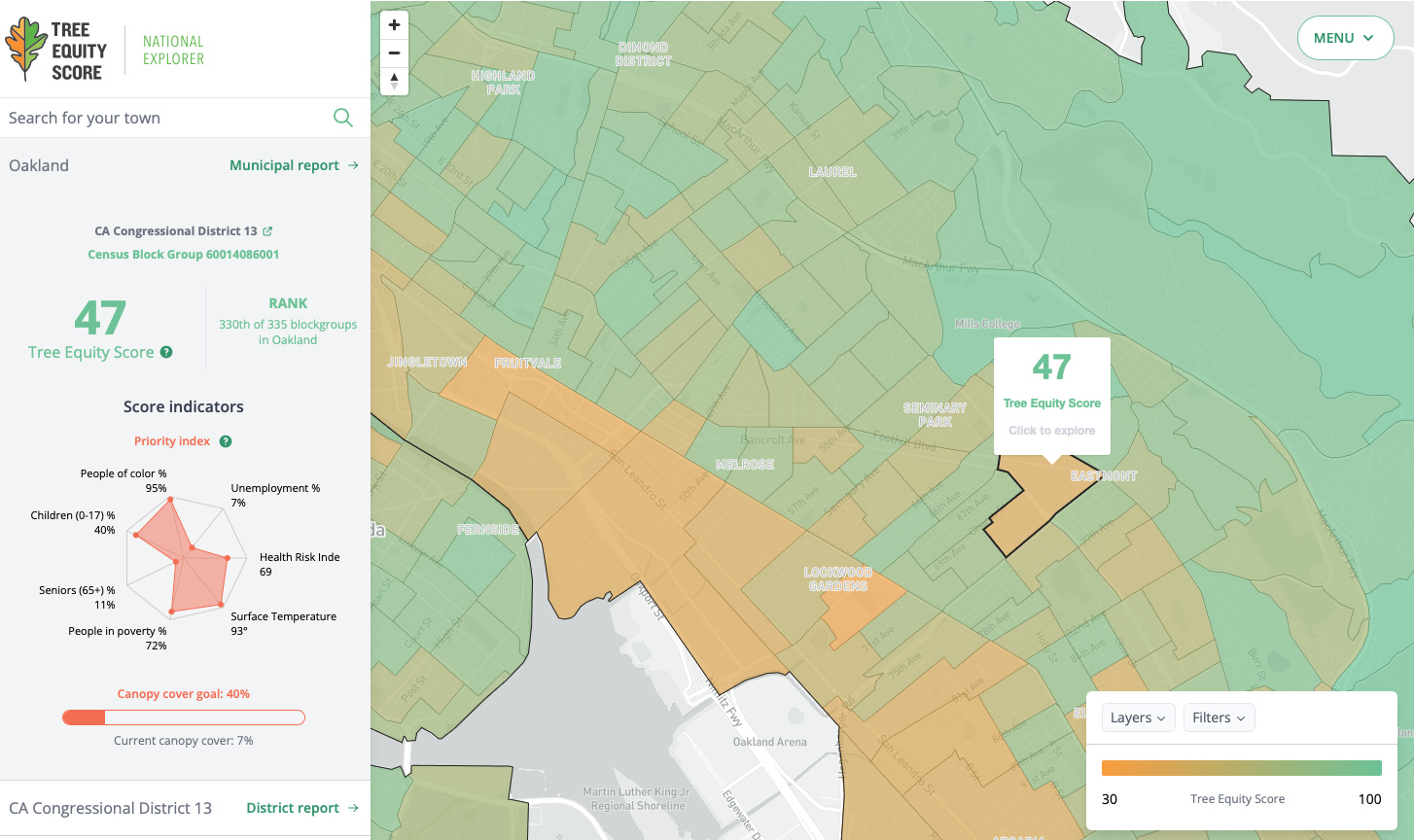

Local access to tree cover and public parks (Tree Equity Score)

Household income level and access to medical facilities

Prevalence of early-age and elderly hospitalizations

With data, we learn that building heat-resilient cities starts with equitable distribution of greenways. Historically, industrial areas and marginalized, low-income communities felt the worst effects of the urban heat waves. According to the Tree Equity Score, neighborhoods with majority people of color enjoy 33% less tree canopy coverage on average than majority white communities and neighborhoods with 90% or more living in poverty enjoy 65% less tree canopy than communities with 10% or less in poverty. Trees don’t only present a financial necessity, but also offer an opportunity to create systemic change.

Scaling climate impact of community organizers

Read through UrbanFootprint’s case studies and you’ll quickly realize how impactful data-backed city planning can be. But it got me thinking — is there a way to combine local policy with urban data to create an engine for community-based climate action? Can we use the data to prevent instead of adapt?

With special attention to climate-specific legislation like the IRA, UrbanFootprint could help create deeper partnerships between local governments and community builders who need better data scale nationwide organizing.

Just like Project Sunroof provides Americans with free access to crucial solar-planning information, UrbanFootprint could function like a public homeowner reference tool. Tied to parcel and permit data, community organizers could create a national decarbonization campaign targeting neighborhoods that would benefit most from incentives. This tool could:

Highlight neighborhood blocks that are eligible for electrification incentives. Community organizers and non-profit developers like Rising Sun could partner to upgrade electrical panels, install solar, and other critical in-home electric infrastructure.

Integrate with a growing network of EV chargers, micro-mobility infrastructure, and more. Homes that lack access to public transit or have low walk scores will benefit from alternate zero emission transportation such as bike share, EV car share, community EV chargers, and even scooters.

Prioritize access to DC fast charging stations. In neighborhoods with a high level of multi-family property and limited access to parking, access to fast charging stations will help promote the equitable transition to EVs.

Identify which homes lack access to private rooftop solar. Homes that lack access to available panel upgrades, share roofs, or have heavy tree cover miss the opportunity to produce electricity for themselves. Creating a community solar farm could provide necessary micro-grid infrastructure for more remote or inaccessible areas.

Make insights accessible to the layperson. Yes, AI-enabled chat is buzzy right now (I even get texts from my 70s father-in-law about ChatGPT. Legend.). But could a chatbot be the answer for community organizers and policymakers that are trying to find a quick, data-backed answer for “Where should we plant trees in Oakland? Where should we install community EV chargers?”

Leading by example

Data doesn’t only exist to provide insights to create action plans — it’s a track record of what works and what doesn’t. With access to decades of urban forestry data, city managers looking to deploy their UFP can look to other cities with similar characteristics. Using urban density, land use, and geographic characteristics (among other attributes) will help cities develop a reforestation plan that’s backed by proven, empirical evidence.

Goal setting can and should be a shared endeavor. Case studies and best practices like this UFP from the City of Boston can go a long way for small cities looking to establish and their own urban forestry plans. For smaller towns, urban data teams are few and far between. What UrbanFootprint has done is made critical urban data available without the need to learn data programming.

That’s a very important cause for many American cities, especially Southern ones.